Selected excerpts from ‘The Plot Against the NHS’ by Colin Leys and Stewart Player. Chapter One is available here. I highly recommend this book available from Merlin Press for £10.

I got my copy yesterday so I have yet to complete it. The book identifies intense lobbying by commercial interests resulting in the privatisation of ancilliary NHS services under Thatcher, covert privatisation of the NHS under Blair’s New Labour administration and Andrew Lansley’s overt privatisation under the current Conservative and Liberal-Democrat coalition government. It draws a picture of the private sector unable to compete with the NHS in terms of cost or quality and the private sector being given excessive, hugely favourable terms. Patricia Hewitt, Alan Milburn and John Reid are identified as covert privateers ‘marketers’ under the Blair administration.

p51

By late 2008 the crisis was at it’s height. Lehmann Brothers was history, Northern Rock had been nationalized along with Lloyds and the Royal Bank of Scotland, and the government’s debt was on course to reach 70 per cent of national income, up from around 40 per cent for most of the decade. In this situation it was obvious that public spending was going to suffer. How would this affect the NHS?

According to the Department of Health, the management consultants McKinsley (where Dr Dash was by now a partner in the company’s London office) were instructed in February 2009 ‘to provide advice on how commissioners might achieve world class NHS productivity to inform the second year of the world class commissioning assurance system and future commissioner development. The advice from McKinsley … was provided in March 2009.’ But the advice McKinsley gave actually tells a different story.

We don’t know what assumptions they were told to make but it looks as if they were told or at least encouraged to assume that NHS spending would remain constant for the next five years, and asked how productivity could be increased to cope with the rise in demand over that time. Their conclusion was that in order to find enough savings to meet the rising cost of providing health care over those years the NHS might have to shed ten per cent of it’s staff. When the press got hold of the report in September 2009 there was a furious reaction from the NHS workforce.

Health ministers then said that the report had been rejected, and even then it had been commissioned without their authority.

…

p54

In October 2010 the coalition government announced that it would continue to raise NHS spending in real terms (based on the general consumer price index) over the next four years – the figure actually claimed was an annual rise of 0.1 per cent. As a result most people outside the NHS assumed that the cuts would now stop. But the reality was different. For one thing, the NHS was told to transfer £2.1 billion to local authorities over the next five years as part of a drive to move patients out of hospitals and into more ‘cost-effective’ social or community care. So the NHS budget was actually being cut. And the NHS’s costs (for drugs, equipment, electricity, etc) would go on rising faster than the general cost of living, so that even if its budget stayed more or less constant it would soon be too small to cover all the bills.

On top of this, people’s healthcare needs (or ‘patient demand’, as today’s policy-makers call patients’ needs) would also go on rising as people got older, or more obese, or more depressed – and as more of them became unemployed. The economic crisis was thus also a healthcare crisis, in which drastic measures could be presented as being unavoidable, measures of ‘last-resort’ – even if they implied the end of a high-quality health service equally available to all.

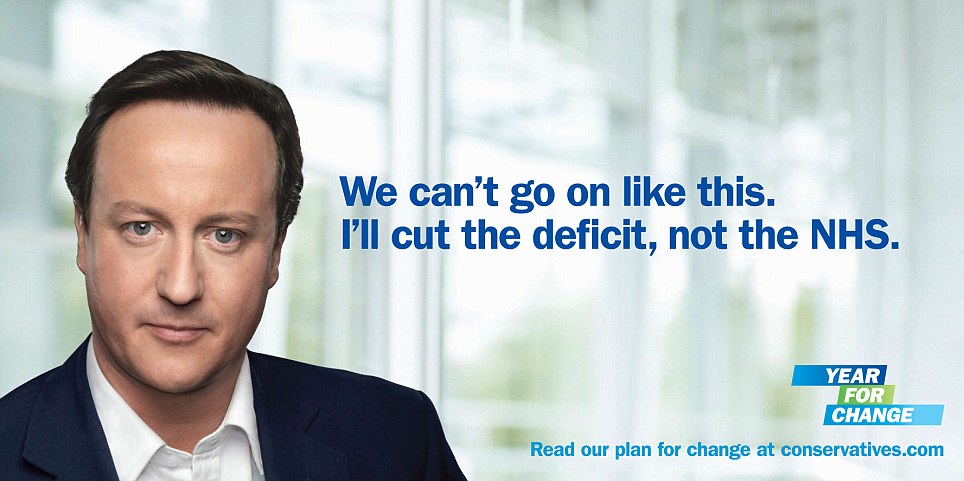

Which was pretty much what the new Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, decided to do, with proposals for yet another NHS reorganization – a reorganization not only un-mentioned in the election campaign, but one that flatly contradicted David Cameron’s pledge not to undertake any more ‘top-down reorganizations’ in the NHS. Everyone noticed, of course: but the coalition’s argument that the financial crisis meant that all previous bets were off proved effective – even if at first most people couldn’t quite see what Lansley was driving at. All comentators agreed in calling his proposals the most important changes in the NHS since it was set up – but what exactly did the changes mean? And were they really so different from what had been covertly planned for ten years or more under New Labour?

…

p68

By the time of the 2010 election a fairly clear picture of what the future NHS market would be like had emerged amoung health policy insiders. Influenced by a decade of exposure to US policy advice, and especially by the link with Kaiser Permanente, they envisaged an NHS that was already much closer to being a kitemark attached to a wide variety of provider organizations and systems than people outside the policy-making circle realized.

They imagined a radically reduced NHS hospital sector, with the surviving NHS foundation trusts focused intently on financial success. They envisaged the bulk of outpatient care being transferred out of hospitals into local, cheaper settings, which would be privately built and owned (as so many NHS hospitals already were, through PFI), or jointly owned with ‘entrepreneurial’ clinicians. They envisaged a growing number of the remaining NHS hospitals being run by private companies. They imagined specialist clinicians becoming increasingly self-employed, rather than working on a salary for a single foundation trust, and selling their services to a mix of public and private organizations.

They expected a growing proportion of patients with chronic illnesses to have fixed budgets for their care, and they accepted that top-ups, for which insurance companies would provide insurance plans, would become a normal form of co-payment, as they already were for some life-prolonging cancer drugs. They expected PCTs to be using private healthcare corporations to help them commission services in a more sophisticated way, or doing it for them, and so driving foundation trusts to become more focused on economy and driving more work to private providers. Fundamentally, they anticipated a replication of many of the structures and values of US managed care.

No one who was familiar with this imagined future could have been surprised by the contents of Lansley’s White Paper of July 2010, or the Health and Social Care Bill of January 2011. The only people likely to be surprised were the public, with whom the marketizers had chosen not to share their vision.