Climate Crisis to Cost Global Economy $38 Trillion a Year by 2050

Original article by OLIVIA ROSANE republished from Common Dreams under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

“This clearly shows that protecting our climate is much cheaper than not doing so, and that is without even considering noneconomic impacts such as loss of life or biodiversity,” a new study’s lead author said.

The climate crisis will shrink the average global income 19% in the next 26 years compared to what it would have been without global heating caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels, a study published in Nature Wednesday has found.

The researchers, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), said that economic shrinkage was largely locked in by mid-century by existing climate change, but that actions taken to reduce emissions now could determine whether income losses hold steady at around 20% or triple through the second half of the century.

“These near-term damages are a result of our past emissions,” study lead author and PIK scientist Leonie Wenz said in a statement. “We will need more adaptation efforts if we want to avoid at least some of them. And we have to cut down our emissions drastically and immediately—if not, economic losses will become even bigger in the second half of the century, amounting to up to 60% on global average by 2100.”

“I am used to my work not having a nice societal outcome, but I was surprised by how big the damages were.”

Put in dollar terms, the climate crisis will take a yearly $38 trillion chunk out of the global economy in damages by 2050, the study authors found.

“That seems like… a lot,” writer and climate advocate Bill McKibben wrote in response to the findings. “The entire world economy at the moment is about $100 trillion a year; the federal budget is about $6 trillion a year.”

This means that the costs of inaction have already exceeded the costs of limiting global heating to 2°C by six times, the study authors said. However, limiting warming to 2°C can still significantly reduce economic losses through 2100.

“This clearly shows that protecting our climate is much cheaper than not doing so, and that is without even considering noneconomic impacts such as loss of life or biodiversity,” Wenz said.

The damages predicted by the study were more than twice those of similar analyses because the researchers looked beyond national temperature data to also incorporate the impacts of extreme weather and rainfall on more than 1,600 subnational regions over a 40-year period, The Guardian explained.

“Strong income reductions are projected for the majority of regions, including North America and Europe, with South Asia and Africa being most strongly affected,” PIK scientist and first author Maximilian Kotz said in a statement. “These are caused by the impact of climate change on various aspects that are relevant for economic growth such as agricultural yields, labor productivity, or infrastructure.”

However, Wenz told the paper that the paper’s projected reduction was likely a “lower bound” because the study still doesn’t include climate impacts such as heatwaves, tropical storms, sea-level rise, and harms to human health.

Unlike previous studies, the research predicted economic losses for most wealthier countries in the Global North, with the U.S. and German economies shrinking by 11% by mid-century, France’s by 13%, and the U.K.’s by 7%. However, the countries set to suffer the most are countries closer to the equator that have lower incomes already and have historically done much less to contribute to the climate crisis. Iraq, for example, could see incomes drop by 30%, Botswana 25%, and Brazil 21%.

“Our study highlights the considerable inequity of climate impacts: We find damages almost everywhere, but countries in the tropics will suffer the most because they are already warmer,” study co-author Anders Levermann, who leads Research Department Complexity Science at PIK, said in a statement. “Further temperature increases will therefore be most harmful there. The countries least responsible for climate change, are predicted to suffer income loss that is 60% greater than the higher-income countries and 40% greater than higher-emission countries. They are also the ones with the least resources to adapt to its impacts.”

Wenz told The Guardian that the results were “devastating.”

“I am used to my work not having a nice societal outcome, but I was surprised by how big the damages were. The inequality dimension was really shocking,” Wenz said.

Levermann said the paper presented society with a clear choice:

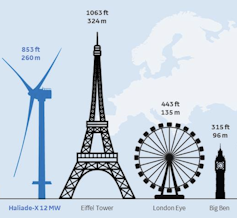

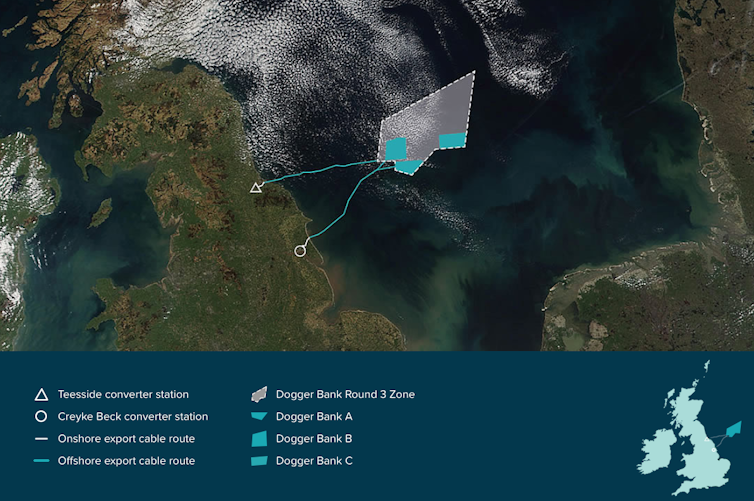

It is on us to decide: Structural change towards a renewable energy system is needed for our security and will save us money. Staying on the path we are currently on, will lead to catastrophic consequences. The temperature of the planet can only be stabilized if we stop burning oil, gas, and coal.

McKibben, meanwhile, argued that the findings should persuade major companies to embrace climate action for self-interested reasons. He noted that most corporate emissions come from how company money is invested by banks, particularly in the continued exploitation of fossil fuel resources.

“If Amazon and Apple and Microsoft wanted to avoid a world where, by century’s end, people had 60% less money to spend on buying whatever phones and software and weird junk (doubtless weirder by then) they plan on selling, then they should be putting pressure on their banks to stop making the problem worse. They should also be unleashing their lobbying teams to demand climate action from Congress,” McKibben wrote.

“These people are supposed to care about money, and for once it would help us if they actually did,” he continued. “Stop putting out ads about how green your products are—start making this system you dominate actually work.”

Original article by OLIVIA ROSANE republished from Common Dreams under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

- By 2030, Poor Nations Will Need $2.4 Trillion Per Year To Fight Climate Crisis: Report ›

- Rich Nations Have Delivered Mere ‘Pittance’ To Help East Africa Tackle Climate Crisis: Oxfam ›

- Senator Markey And Rep. Ocasio-Cortez Introduce Civilian Climate Corps For Jobs And Justice To Rebuild America ›

- 2023’S Costliest Weather Disasters Reveal ‘Double Inequality’ Of Climate Crisis ›

- Consumerism, Inequality, And The Climate Crisis ›