As disasters and heat intensify, can the world meet the urgency of the moment at the COP28 climate talks?

Shutterstock

Brendan Mackey, Griffith University

Eight years ago, the world agreed to an ambitious target in the Paris Agreement: hold warming to 1.5°C to limit further dangerous levels of climate change.

Since then, greenhouse gas emissions have kept increasing – and climate disasters have become front page news, from mega-bushfires to unprecedented floods.

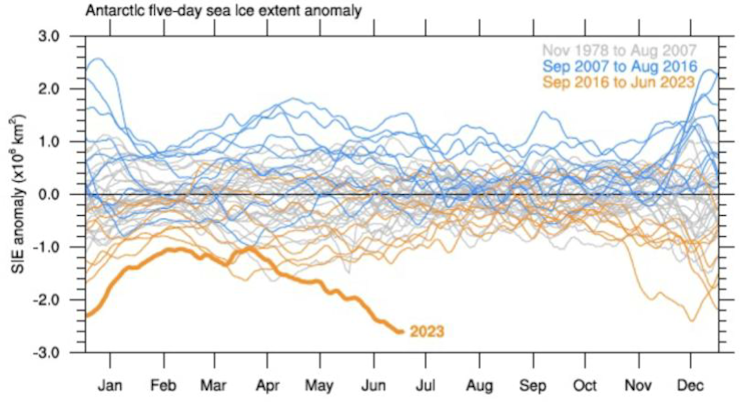

In 2023, the world is at 1.2°C of warming over pre-industrial levels. Heatwaves of increasing intensity and duration are arriving around the world. We now have less than 10 years before we reach 1.5°C of warming.

This week, the COP28 climate talks will begin against a backdrop of evermore strident warnings from climate scientists and world leaders. United Nations chief António Guterres has warned climate action is “dwarfed by the scale of the challenge” and that we have “opened the gates of hell”. In his latest climate letter, Pope Francis quotes bishops from Africa who dub the climate crisis a “tragic and striking example of structural sin”.

NOAA, CC BY-SA

In the United Arab Emirates, the 198 nations in the UN’s climate framework will gather for COP28. Can we expect to see real progress – or half-measures?

Watch for these three key issues facing negotiators.

1. Taking stock of progress on climate action

This year, a critical issue will be the global stocktake, the key mechanism designed to ratchet up climate ambition under the 2015 Paris Agreement. This is the first time each nation’s emission cut targets and benefits from climate adaptation or economic diversification plans have been assessed.

The stocktake reveals what track we are on. Do the combined emission cut promises from all countries mean we can limit warming to 1.5°C? If not, what is the “emissions gap” – and how much more ambitious do nation’s emission reductions need to be?

There’s been progress, but not nearly enough. If all national emissions pledges became a reality, global warming would peak between 2.1-2.8°C.

That leaves an emissions gap of around 22.9 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent over the period to 2030.

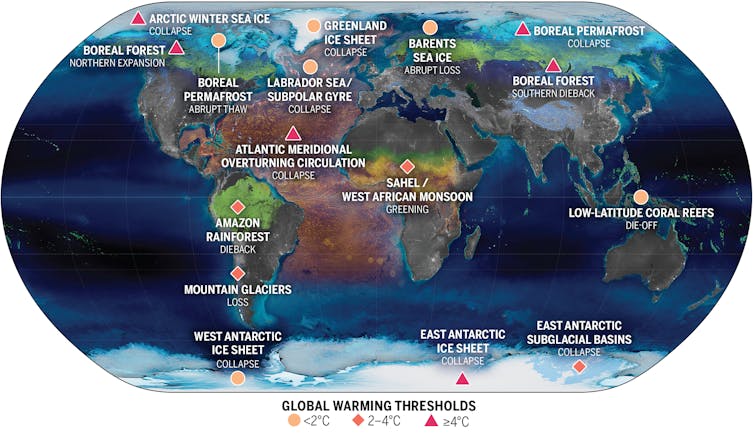

It is very good that the worst-case scenarios – unchecked warming and 4+ degrees of global heating by 2100 are now looking unlikely. But a 2°C world would bring unacceptable harm and irreversible damage.

We’ll need much more ambitious targets and support to cut global greenhouse gas emissions 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035 compared with 2019 levels if we are to reach net zero CO₂ emissions by 2050 globally. A major measure of COP28’s success will be whether the major emitting nations agree on more ambitious emission reduction actions.

2. Who pays for climate loss and damage?

For decades, nations have wrestled over the fraught question of who should pay for loss and damage resulting from climate change.

Now we’re close to finalising arrangements for the new Loss and Damage Fund. This will be the second major issue for negotiators at COP28.

So far, governments have drawn up a blueprint for the new fund. Expect to see debate over who will manage the fund – the World Bank? A UN agency? – and whether emerging economies such as China will provide funds. To date, there’s no target for how much money the fund will hold and disburse. The blueprint must be formally adopted at COP28 before it can begin operating.

Why a new fund? Other climate finance commitments are aimed at cutting emissions or helping societies adapt to climate impacts. This fund deals specifically with the loss and damage from the unavoidable impacts of climate change, like rising sea levels, prolonged heatwaves, desertification, the acidification of the sea, extreme weather and crop failures.

Think of the damage from the unprecedented floods in Pakistan or Libya, for instance.

Shutterstock

3. Where’s the climate finance?

A major issue in climate negotiations is how countries can transform their economies so they are “climate ready”, with lower emissions and boosted resilience. For developing countries, this requires massive levels of investment and new technologies to let them “leapfrog” fossil fuel dependency.

This is likely to be a critical sticking point. To date, climate finance has flowed too slowly. Under the Paris Agreement, rich countries promised to provide funds of A$150 billion a year every year. This has been slow in coming, though it is nudging closer, with $130 billion flowing in 2021.

Unless we see significant progress on climate finance – including making the Loss and Damage Fund a reality and meeting the existing commitments – we’re unlikely to see progress on other key issues such as ratcheting up emission cuts under the stocktake mechanism, phasing out fossil fuels and work on preserving biodiversity.

How do you build a 198-government consensus?

One reason climate negotiations advance slowly is the need for consensus.

All 198 governments must agree on each decision. This means any one nation or group of countries can block a proposal or force the wording to be changed in order for it to be approved.

The votes of less wealthy countries – including small island nations and least developed countries – therefore carry as much weight as the G20 nations, who account for about 85% of global GDP. This has in the past worked to increase the level of climate action, including the focus on 1.5°C as the global warming target.

The COP28 President is Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, who has attracted controversy due to the fact he heads the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. Expect to see considerable debate over wording. Will governments agree to the “phasing down of fossil fuels” or just the “phasing down of unabated fossil fuels”?

It might sound like quibbling but it’s not – the second option, for instance, implies the heavy use of yet-to-be-proven carbon capture and storage technologies and offsets.

Sultan al-Jaber has, to his credit, promoted some progressive agenda items including a focus on the conservation, restoration, and sustainable management of nature to help achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Here, there are welcome commonalities with the major global biodiversity pact struck late last year, the Global Biodiversity Framework, aimed at stemming the extinction of species and degradation of ecosystems. Healthy ecosystems store carbon and help people adapt to the climate change already here.

As nations prepare for a fortnight of intense negotiation, the stakes are higher than they have ever been. Now the question is – can the world community seize the moment? ![]()

Brendan Mackey, Director, Griffith Climate Action Beacon, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.