After COP27, all signs point to world blowing past the 1.5 degrees global warming limit – here’s what we can still do about it

Peter Schlosser, Arizona State University

The world could still, theoretically, meet its goal of keeping global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius, a level many scientists consider a dangerous threshold. Realistically, that’s unlikely to happen.

Part of the problem was evident at COP27, the United Nations climate conference in Egypt.

While nations’ climate negotiators were successfully fighting to “keep 1.5 alive” as the global goal in the official agreement, reached Nov. 20, 2022, some of their countries were negotiating new fossil fuel deals, driven in part by the global energy crisis. Any expansion of fossil fuels – the primary driver of climate change – makes keeping warming under 1.5 C (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared to pre-industrial times much harder.

Attempts at the climate talks to get all countries to agree to phase out coal, oil, natural gas and all fossil fuel subsidies failed. And countries have done little to strengthen their commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the past year.

There have been positive moves, including advances in technology, falling prices for renewable energy and countries committing to cut their methane emissions.

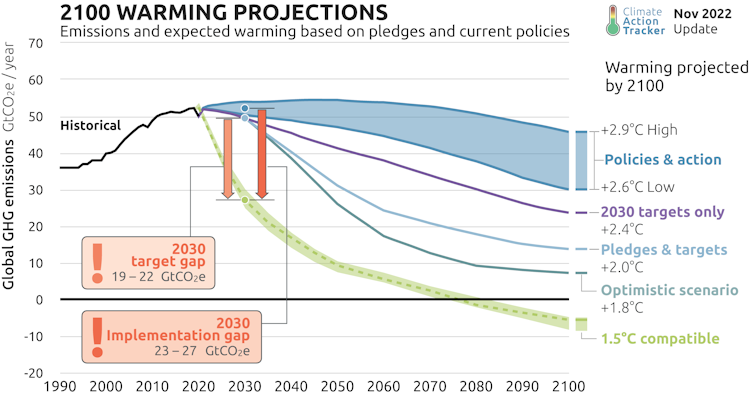

But all signs now point toward a scenario in which the world will overshoot the 1.5 C limit, likely by a large amount. The World Meteorological Organization estimates global temperatures have a 50-50 chance of reaching 1.5C of warming, at least temporarily, in the next five years.

That doesn’t mean humanity can just give up.

Why 1.5 degrees?

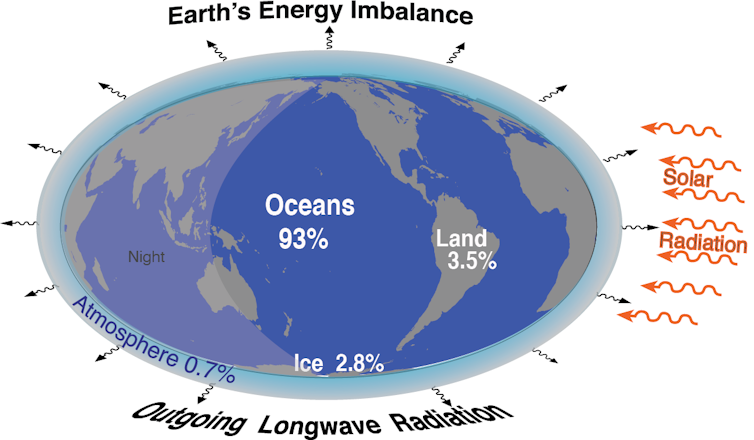

During the last quarter of the 20th century, climate change due to human activities became an issue of survival for the future of life on the planet. Since at least the 1980s, scientific evidence for global warming has been increasingly firm , and scientists have established limits of global warming that cannot be exceeded to avoid moving from a global climate crisis to a planetary-scale climate catastrophe.

There is consensus among climate scientists, myself included, that 1.5 C of global warming is a threshold beyond which humankind would dangerously interfere with the climate system. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/temperature-anomaly?time=earliest..latest

We know from the reconstruction of historical climate records that, over the past 12,000 years, life was able to thrive on Earth at a global annual average temperature of around 14 C (57 F). As one would expect from the behavior of a complex system, the temperatures varied, but they never warmed by more than about 1.5 C during this relatively stable climate regime.

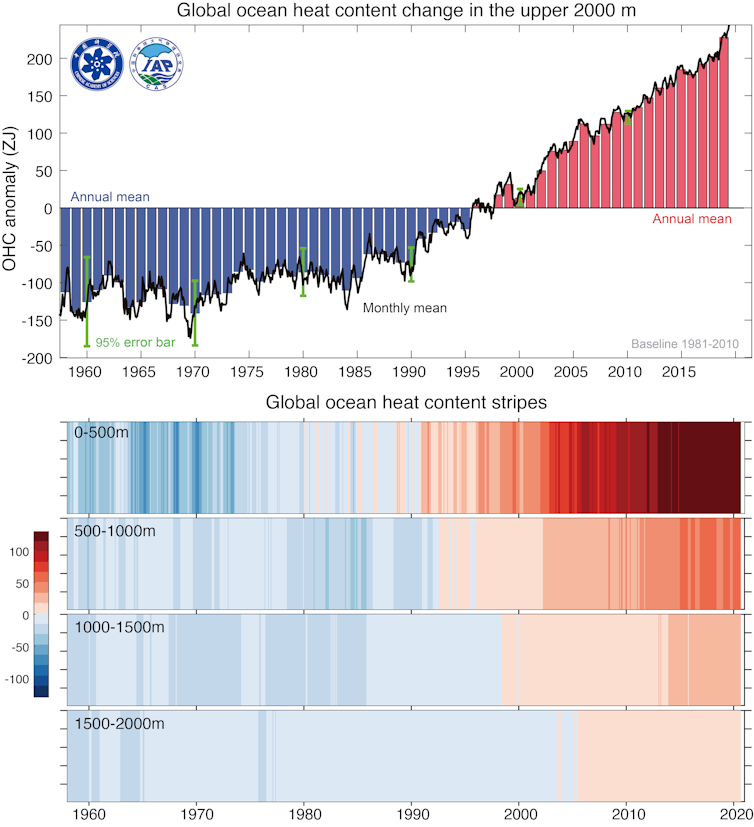

Today, with the world 1.2 C warmer than pre-industrial times, people are already experiencing the effects of climate change in more locations, more forms and at higher frequencies and amplitudes.

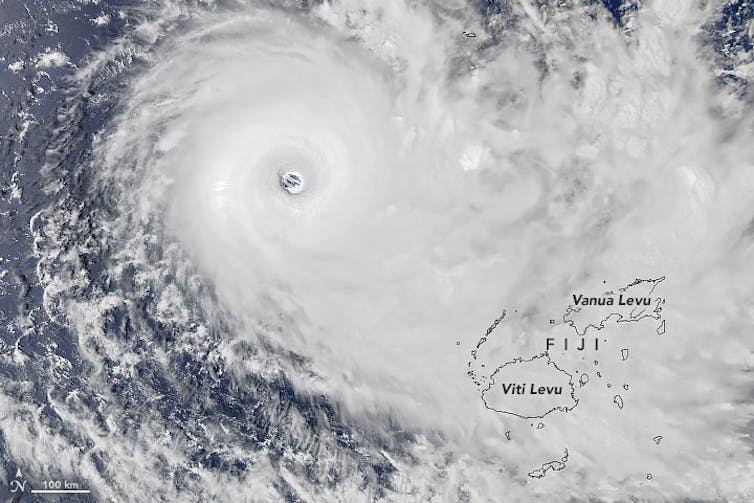

Climate model projections clearly show that warming beyond 1.5 C will dramatically increase the risk of extreme weather events, more frequent wildfires with higher intensity, sea level rise, and changes in flood and drought patterns with implications for food systems collapse, among other adverse impacts. And there can be abrupt transitions, the impacts of which will result in major challenges on local to global scales. https://www.youtube.com/embed/MR6-sgRqW0k?wmode=transparent&start=0 Tipping points: Warmer ocean water is contributing to the collapse of the Thwaites Glacier, a major contributor to sea level rise with global consequences.

Steep reductions and negative emissions

Meeting the 1.5 goal at this point will require steep reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, but that alone isn’t enough. It will also require “negative emissions” to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide that human activities have already put into the atmosphere.

Carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for decades to centuries, so just stopping emissions doesn’t stop its warming effect. Technology exists that can pull carbon dioxide out of the air and lock it away. It’s still only operating at a very small scale, but corporate agreements like Microsoft’s 10-year commitment to pay for carbon removed could help scale it up.

A report in 2018 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change determined that meeting the 1.5 C goal would require cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 50% globally by 2030 – plus significant negative emissions from both technology and natural sources by 2050 up to about half of present-day emissions.

Can we still hold warming to 1.5 C?

Since the Paris climate agreement was signed in 2015, countries have made some progress in their pledges to reduce emissions, but at a pace that is way too slow to keep warming below 1.5 C. Carbon dioxide emissions are still rising, as are carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere.

A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program highlights the shortfalls. The world is on track to produce 58 gigatons of carbon dioxide-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 – more than twice where it should be for the path to 1.5 C. The result would be an average global temperature increase of 2.7 C (4.9 F) in this century, nearly double the 1.5 C target.

Given the gap between countries’ actual commitments and the emissions cuts required to keep temperatures to 1.5 C, it appears practically impossible to stay within the 1.5 C goal.

Global emissions aren’t close to plateauing, and with the amount of carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere, it is very likely that the world will reach the 1.5 C warming level within the next five to 10 years.

How large the overshoot will be and for how long it will exist critically hinges on accelerating emissions cuts and scaling up negative emissions solutions, including carbon capture technology.

At this point, nothing short of an extraordinary and unprecedented effort to cut emissions will save the 1.5 C goal. We know what can be done – the question is whether people are ready for a radical and immediate change of the actions that lead to climate change, primarily a transformation away from a fossil fuel-based energy system.

Peter Schlosser, Vice President and Vice Provost of the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.